By: Shreyashi Roy

October 25 2022

Misleading: Gandhi was given ₹100 a month in Yeravda Central Prison as an allowance for personal maintenance.

The Verdict Misleading

Gandhi had refused to accept aid from the British who would make such allocations for the provision of medicines etc. to political prisoners.

Context:

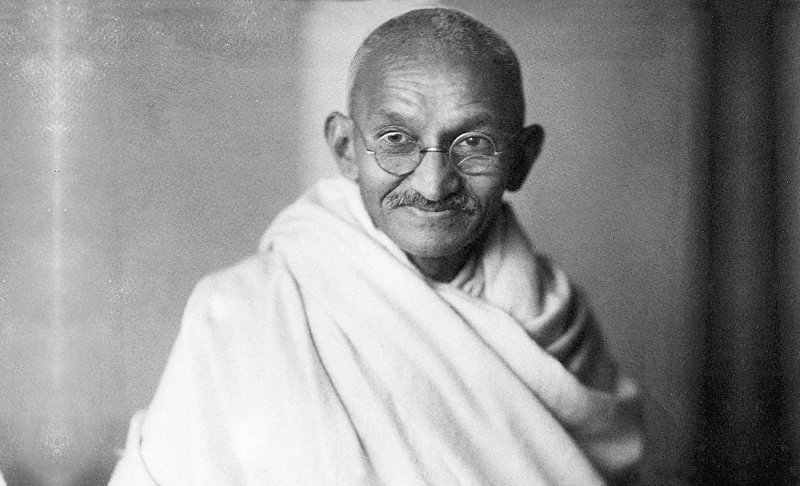

Mahatma Gandhi, one of India's most famed leaders and freedom fighters, has long been the topic of fake viral news. One such claim, which has been doing the rounds on social media lately, insists that when Gandhi was imprisoned in Pune's Yeravda Central Jail in 1930, he was given ₹100 a month as an allowance for personal maintenance. This claim started making the rounds on social media around October 3, a day after Gandhi Jayanti—Gandhi's birth anniversary—was observed in India, and was amplified by several right-wing supporters. Several people shared the claim on social media along with documents they alleged supported this 'discovery,' and among them was writer and self-proclaimed political commentator Ajit Datta, and historian Vikram Sampath. Their tweets racked up thousands of retweets and likes and began a battle of opinions. Some have sought to insinuate that Gandhi was paid this money by the then-British Government in India, effectively making him their stooge. Many refuted and questioned the claim, while many stated that this showed Gandhi's ‘true nature and intentions’.

In fact:

Logically’s research shows that the truth is misrepresented in these viral claims which rely on selective sharing of documents and twisting of facts. Firstly, Gandhi was not the only political prisoner being offered this sum. Secondly, the freedom fighter even refused to accept the amount from the British government.

Those sharing the misleading claims posted some pages from documents carrying a 'National Archives of India watermark. In his tweet, Vikram Sampath, who has penned a biography of the polarising activist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, said the documents were available on Indian Culture, a Government of India website, and also provided a link to access the documents. These documents, a series of correspondences between the Bombay Government and officials of the Central Government, dated between May and September 1930, deal with the "treatment" of Gandhi while confined in prison under the Bombay Regulation Act XXV of 1827. We found that the document repeatedly mentions a sum of ₹100 per month that was to be granted to Gandhi as allowance for "personal maintenance" or "personal upkeep" while detained as a State prisoner in the jail. The local Bombay Government sanctioned the allowance and it was consequently approved by the Home Department of the Government of India. Many of the letters and telegrams in the document were exchanged back and forth to discuss the logistics of meeting this expense.

Several people on social media are using the documents to allege that Gandhi was receiving a pension of sorts from the British, comparable to that received by Savarkar. While Savarkar is revered by the right-wing ecosystem in India, many opposition leaders, and liberal and leftist thinkers have called him a British loyalist who also received a pension from the colonial government after writing mercy petitions to them asking to be freed from jail.

On going through these documents made available publicly, we noticed that it does not mention that Gandhi was being paid this money directly, like a pension (a claim made by many of those sharing the documents). Further, as mentioned before, it is not a notable exception made for Gandhi alone.

One of the letters made available with the documents says that the Bombay Government's press communique about the arrest of Gandhi stated that "every provision will be made for his health and comfort." As the document notes, the ₹100 was an expenditure incurred on account of an allowance for Gandhi while he was a State prisoner. "As Mr. Gandhi is being detained under the Bombay Regulation XXV of 1827, arrangements for his care and treatment in accordance with the terms of the Bombay Regulation will be made by the local government," states a telegram from the Secretary of State to the Bombay Government dated May 1930. One handwritten letter calls it "the detention allowance…granted to Mr. Gandhi while in jail," the expenditure on which was to be debited to Central revenues under the head Political - Refugees and State Prisoners. The Bombay Government's resolution passed on May 5, 1930, the same day as Gandhi was detained by the police, sanctioned the allowance for Gandhi, and stated that the amount should be remitted to the Superintendent of the Yeravda Central Prison. Additionally, one typewritten letter among the documents mentions that similar charges were also debited on account of the Bengali State prisoner Satish Chandra Pakrashi in June 1927.

We also reviewed several documents available on Indian Culture and Abhilekh Patal, a portal of the National Archives of India, which show that the kind of allowance offered to Gandhi was also given to other prisoners, and was indeed a common practice. A series of correspondences about the increase in the allowance granted to State prisoner Bhawani Sahai in 1933, detained in Allahabad's Naini prison, detail its nature— for daily dietary needs, bedding, and clothes. The letters explain that Sahai was granted a lump sum of ₹60 on admission to the prison, which was supplemented later by a sum of ₹56, apart from his monthly allowance of ₹18. One of the letters in the file makes a key point: "We have fixed monthly allowances for our State prisoners in all cases and may give Bhawani Sahai an allowance of Rs 18 monthly instead of the Rs 10 he now gets."

Another file shows that in January 1910, State prisoner BC Nag, confined in Central Prison, Fatehgarh, Uttar Pradesh, asked for an increase in his allowance of ₹70 per month, owing to a need for law books, other reference books for study, and an extra supply of fruits. This request was granted by the British government as well. Yet another file from 1932 puts forward a list of State prisoners in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay and the amount of personal and family allowance granted to them. The list included names of both high-profile leaders and less well-known figures, all of whom received personal allowances while in prison, and some of whose dependants and family members were also given a monthly sum.

Further, a 1996 thesis written for the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, by Ujjwal Kumar Singh, author, and Reader of the Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, throws more light on the nature of these personal allowances. In his thesis titled 'Political Prisoners in India, 1920-1977', Singh writes about Bengal prisoners: "Government was empowered to provide an individual allowance for the detenu, and family allowance for maintenance of a ‘near relative’ or his ‘dependents’ based on their ‘rank in life.’ Allowances given to the individual detenu included the daily dietary allowance, monthly personal allowance and a yearly allowance for clothing, bedding and miscellaneous articles. The government also paid insurance premia in certain cases so as to prevent damage to a prisoner’s estate." Singh draws upon Section 21 of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment, 1925, and a Telegram dated May 29, 1932, from the Home Department, Government of India to the Secretary of State to reach these conclusions.

Noted New–Delhi based historian S Irfan Habib, whose works revolves around modern political history, also confirmed Logically’s findings. On reviewing some of the documents, Habib said, "Granting of allowance to prisoners was a normal practice by the British government... They used to have a budget for the expenses of all prisoners. The allowance was for his (Gandhi's) maintenance if he needed any medicine or any other support. And that money was not directly given to the concerned person or sent to their account."

In a video uploaded on his YouTube channel ‘The Credible History’, author and renowned historian Ashok Kumar Pandey has also refuted the viral claims. In the video, Pandey mentioned that autobiographies or biographies of leading figures of that period and jail rules show that every prisoner had a budget for them, at the cost of the local government, which was used for food and other requirements. He explains that the allowance was not something that was a handout or a bestowment upon Gandhi but a provision for expenditure on his needs while imprisoned. In another video posted on his verified Twitter handle, Pandey also referred to the same documents shared by Sampath and others, pointing out that the letters clearly show that this money was meant to be spent on Gandhi's health and expenses while in prison. This money was meant to go to the jailor, who would then spend it on Gandhi's needs. Speaking to Logically, Pandey said, "The British Government knew the importance of Gandhi. They knew perfectly well that any health hazard Gandhi suffered during jail term could create havoc in the rest of the country, and that's why they wanted to take care of him. Making it an issue or terming it as a pension is ridiculous”.

Pandey also pointed that Gandhi had, however, rejected to accept the aid offered by the British. "The document in question is not an exclusive one. Gandhi referred to it in a letter collected in ‘The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi-Volume 49’ wherein he clearly rejected the government proposal. This was neither a pension nor any special allowance but a budget for the maintenance of Gandhi while in Yervada Jail. The letter is easily available online, and anyone can check that Gandhi never made any demand for any kind of special treatment in jails."

Pandey was referring to a letter Gandhi had written to a British official Major E Doyle on May 10, 1930 ostensibly after a conversation with him. This letter was written just five days after the resolution sanctioning the allowance, and can be found on page 273 of Volume 49 of The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

"Having thought over our conversation, I have come to the conclusion that I must avoid, as much as possible, the special privileges offered to me by the Government!" Gandhi writes in the letter. He adds that he does not want books and newspapers through the government, saying that he would like permission to send for some papers himself, which he lists. Further, he refuses to accept the allowance the government has sanctioned, agreeing only to let them cover his basic food costs. "The Government have suggested Rs.100 as monthly allowance. I hope I shall need nothing near it. I know that my food is a costly affair. It grieves me, but it has become a physical necessity with me," Gandhi writes. The letter continues: "Neither you nor the government will, I hope, consider me ungrateful for not accepting all the facilities offered to me. It is an obsession (if it is to be so called) with me that we are all living at the expense of the toiling semi-starved millions. I know too that the saving caused by my economy can but be an infinitesimal drop in the limitless ocean of waste I see going on round me, whether in prison or outside of it—much more out of it. I admit nevertheless it is given to man only to do very little. He dare not omit to do that little." Gandhi ends the letter by making only one request—that he not be kept isolated from his fellow satyagrahis (those who follow the path of non-violence). Hence, it is clearly proved that Gandhi refused to accept the provision being made for him by the British government.

Habib also reiterated that Gandhi’s letter showed that he objected to accepting any kind of assistance from the British apart from provisions for food. "That's what he's writing in this letter; he has stated that he needs no money at all. Gandhi is questioning the need of the British to spend any money on him." Speaking about those spreading misleading claims about Gandhi, Habib said, “These people are using the documents to malign Gandhi, and justify what Savarkar was getting from the British. Savarkar's case was very different, he was getting ₹60 per month, which went into his account. It was a pension that he accepted and kept insisting that it be increased."

It should also be noted here that Ajit Datta, who was one among many to amplify the misleading claim on Gandhi, is associated with the right-wing website ‘The Frustrated Indian’ which has often been found indulging in and spreading fake news.

The verdict:

Unlike what many on social media have claimed, Mahatma Gandhi was not being directly paid ₹100 per month by the British government. The shared documents are being misinterpreted to claim that Gandhi was a stooge of the colonial government. In reality, Gandhi's letter shows that he refused to accept this provision, saying that he would not need ₹100, but only what would be required to cover the cost of his food. Additionally, various other documents have proved that many other State prisoners were given the kind of allowance offered to Gandhi. Therefore, we have marked this claim misleading.